Reedsy’s blog has an excellent post on accumulated NaNoWriMo tips. If you haven’t heard of NaNoWriMo, November is National Novel Writing Month, where you challenge yourself to write a 50,000 word novel in thirty days. Quite the challenge.

One of the things I notice from reading unpublished authors’ fantasy novels is that we Americans don’t have a lot of grounding in the ranks of nobility. Kings, dukes, barons: they are more than fancy titles. They actually mean something.

A full treatise on the subject would occupy many pages. This is primer.

- Emperor or Empress: rules an empire of kingdoms

Caesar is the Roman term for their emperor, from which Czar and Kaiser descend. - King or Queen: rules a kingdom

Mahajari or Maharani is the Indian high king or queen. - Archduke or archduchess: rules an archduchy, considered a monarch in his or her own right.

Also Grand Duke or Grand Duchess, basically the same. - Crown Prince: is the acknowledged heir to the throne

The Prince of Wales is England’s Crown Prince; the Dauphin is the Crown Prince of France. - Prince or Princess: the sons, daughters, and grandchildren of the king or queen

Prince is also a generic term for any ruler, particularly amongst themselves. - Duke or Duchess: rules a duchy

There are eleven dukes in the modern England. - Marchess or Marchioness: is a ruler of a land that borders another country.

Also Margrave in Germany. The title originally designated a military commander tasked with defending a border. - Count or Countess: rules a county

In England, they are called Earls. There are about thirty earls in England. - Viscount or Viscountess: is either the ruler of a viscounty or the descendent of deputy of a count

The French use Vicomte. England has three viscounts. In some kingdoms, viscount is not hereditary. - Baron or Baroness: the lowest rank of nobility, barons rule a barony

England has almost sixty barons. This is the bulk of any kingdom’s noble class. - Knights or Dames: this a granted title, not hereditary, that elevates someone into peerage

Military prowess is the surest way to become a knight, but it can and is granted for other services. The King or Queen may delegate his or her ability to knight people or not. Lesser nobles got in trouble for knighting people all the time.

I have a few pieces I go to when I feel the weight of writing getting to me. It’s a tough job, to put to paper these dreams and visions, and to show them to a world that’s way too full of dreams and visions. They have so many to choose from that yours need to shine like the sun.

One is Melinda Mae, by Shel Silverstein.

Have you heard of tiny Melinda Mae,

Who ate a monstrous whale?

That’s what writing feels like sometimes. The secret is small bites, lots of chewing, and persistence.

Jami Gold, paranormal and urban fantasy author, has a great post about Head Hopping, and why it is bad. Give it a read.

If the POV is unclear or changes too frequently, the reader doesn’t form as strong of a connection to the characters.

Jami has an amazing author blog, with over 600 posts on the writing craft. Check it out when you have an afternoon to burn.

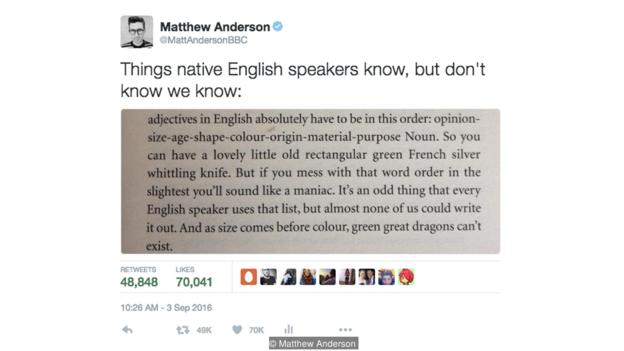

So, you may seen the Twitter post making it’s way around claiming there are rules about language we didn’t know we knew. It’s from the book, The Elements of Eloquence, by Mark Forsyth.

Here is a BBC article on the viral post, and here is the paragraph in question:

Adjectives in English absolutely have to be in this order: opinion-size-age-shape-colour-origin-material-purpose Noun. So you can have a lovely little old rectangular green French silver whittling knife. But if you mess with that word order in the slightest you’ll sound like a maniac. It’s an odd thing that every English speaker uses that list, but almost none of us could write it out.

Stolen from Elmore Leonard’s website directly:

- Never open a book with weather.

- Avoid prologues.

- Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

- Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” . . . he admonished gravely.

- Keep your exclamation points under control. You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose.

- Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.”

- Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

- Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

- Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

- Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

“My most important rule is one that sums up the ten. If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

Podcast: How to Critique

I sat down with J Bryan Jones to join his Coffee House Writer’s Group Podcast to discuss how to critique in a critique group.

It was a fantastic experience. J’s amazing and we ended up chatting for another hour afterwards on fantasy and science fiction, which could have filled another podcast easily.

(We had to stop recording for a moment because I couldn’t get Ernest Hemingway’s name to escape my brain. Super embarrassing for a writer type person. See if you can spot the cut.)

Mentioned in the Podcast:

- Becky Levine’s The Writing & Crique Group Survival Guide: How to Give and Receive Feedback, Self-Edit, and Make Revisions

- Noah Lukeman’s The First Five Pages

- Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat

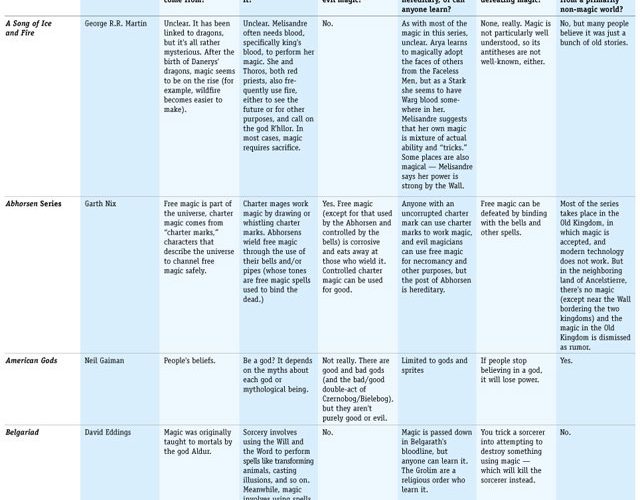

Fantasy novels need rules. For fantasy, the big one is “How does magic work?”

That question literally supplied the plot of my first two novels. And the one I’m working on now.

Someone at Gizmodo has assembled a list for us: Rules of Magic.

TV Tropes is your friend, writer-type people. If you want to see the tropes and clichés of your genre laid bare, this is the place to go. Also, if you have several hours to spend on the internet.